Mara Hoffman's "pop-up" Airstream at the Mondrian Hotel.

Mara Hoffman's "pop-up" Airstream at the Mondrian Hotel.

In the first days of this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach, prominent gallerist Charles Saatchi, a man who was instrumental in the formation of the contemporary art world, issued a screed against the scene assembled in Florida: “Being an art buyer these days is comprehensively and indisputably vulgar. It is the sport of the Eurotrashy, Hedge-fundy, Hamptonites; of trendy oligarchs and oiligarchs; and of art dealers with masturbatory levels of self-regard.” This was a veritable bomb lobbed squarely at the highest echelon of the international arugula set. The message was more than a bit unexpected—Saatchi had built a prolific career out of the establishment he now found himself at odds with. The piece, published in the Guardian, was received with equal measures dismissal and mockery.

Writing about Art Basel in a 2006 essay for the New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl called the aughts “the decade of the art fair,” noting that the Miami festival was “crazy fun.” That decade may be over, but this year marked the 10th annual iteration of the Miami Beach offshoot (presented by UBS, the Swiss tax-code artisan and sometimes investment bank). With the recent addition of Art Hong Kong to the fold, the sun is far from setting on the Art Basel machine.

Prior to boarding American Airlines 1813 on the morning of Dec. 3, I was only peripherally aware of Art Basel and the broader international art world. A series of unlikely circumstances led to my arrival in Miami, joining the wave of weekend warriors showing up three days late to the festivities. The flight was a curious mix of retirees, the egregiously hip, and civilians. I collapsed into my seat and, in an attempt to conjure the appropriate tone for the weekend, fired up Loka People by Sak Noel. As if on cue, two morbidly obese passengers joined me in row 26, abruptly ending the syncopated reverie. I left the song on repeat.

The ride to my hotel was shared with a fellow passenger on the flight, a curator at a museum on the East Coast, his cultural bona fides pre-established by a Comme des Garçons x Fred Perry weekender and a tote bag bearing the name of a major European gallery. A soft-spoken guy in his fifties, the curator confided that he was only stopping by for a day en route to South America, and that he generally was not a fan of Art Basel. Discussion turned to the New Museum on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He commented that it was a “beautiful space” but “too narrow” for good installations, and all too often part of “that whole downtown prank-art” element. He associated this aesthetic with Art Basel. The conversation came to an abrupt end as we pulled up to my hotel. My interlocutor said something about how it looked familiar. Isn’t this a Philippe Starck building? Well, it certainly looks pretty stark, I replied. He didn’t laugh.

* * * * *

I deposited my belongings and made haste to the main event. A small problem, however—the hotel’s taxi-procurement system was choked by the volume of people headed to the convention center. A gaggle of exasperated twenty-somethings complained and chain-smoked Parliaments in front of the glass lobby. A chatty blonde from Chicago, noting my advantageous position in the line, approached me about sharing a ride. She asked if I was in a hurry too. A minivan-cab pulled up.

Somewhere between the sealing of the taxi-sharing pact and the rolling shut of the minivan’s side-doors, an interloper appeared in the seat next to mine. It was American Apparel founder Dov Charney, his entrance a punchline to a joke nobody had made. Striped pants, white polo, boat shoes, hushed urgent conversation on a Verizon Blackberry. “Not now, I’m really pressed. This is a bad time,” he spoke into the phone, which he held at a strange angle, semi-outstretched.

Blonde-from-Chicago appeared completely oblivious to the gravity of the situation. From the third row she made cheerful Midwestern conversation with the cab driver, a man who let us know that he was thoroughly perplexed by Art Basel (but it’s good for business), and bearish on the future of law enforcement in America and Miami in particular (and seatbelt laws, at the micro-level). Oblivious to the audience, he peppered his rants with off-color comments about women on the sidewalk.

I remained a passive participant in the pseudo-conversation, save for the occasional and unnecessarily raucous laugh at the off-color comments in an attempt to get a reaction out of Dov C. I did not succeed in creating a sufficiently unfavorable impression, as when the cab pulled up to the convention center, Charney simultaneously announced his real destination to the driver and, turning to us, flashed a rictus of generosity and dismissed the open wallets. “Don’t worry about it. My treat.”

* * * * *

“The art fair is the new disco,” erstwhile Studio 54 aficionado and high-society scorekeeper Anthony Haden-Guest once pronounced. This seems relatively accurate. Shortly after making my way to the main pavilion, I overheard, at the booth of a prominent New York gallery, a female patron gushing to a gallerist sporting rhinestone-studded denim:

“I looove your jeans”

“Oh thank you—they’re Cavalli. Roberto Cavalli.”

Mostly, however, Art Basel mimics disco culture in more oblique ways. Visitors queue up in front of the convention center, at times waiting over an hour to pay the cover charge ($40 for a day pass). The nucleus of the whole affair, the Miami Beach Conference Center, is an American convention center par excellence—a dated edifice whose architectural influence can be best described as neon-Brutalist. The building has seen its cultural relevance steadily decline since hosting Ali v. Liston in 1964. More recently, the American Academy of Periodontology and the Americas Food and Beverage Show had occupied the Muhammad Ali Hall of Champions, the present name of the structure’s exhibition space. An endless line of black BMW 750i sedans, emblazoned with the Art Basel logo and carrying New Jersey plates, reminded uninitiated passersby that this was no milquetoast professional association.

Art BMW.

Art BMW.

It was hard to imagine that exactly two weeks prior, walking into the same hall would have brought me to some doubtlessly edifying lectures: “Complying with U.S. Import Food and Beverage Entry and Safety Requirements” or “Moderate Sedation for the Contemporary Periodontal Practice.” Sedation certainly would have helped with the audio-visual onslaught that awaited inside the Hall of Champions.

* * * * *

As a holder of an ART BASEL MIAMI BEACH PRESS PASS, I was allowed to use the entrance reserved for gallerists and “VIP” guests, bypassing the hundreds of ticket-holders lined up to enter through a security-type corral. That the door was comically slow may have been deliberate—an intentional manipulation designed to accentuate the cachet. Once inside, the same phenomenon reproduced itself with greater visibility. A walled-off lounge extended the aura of exclusion, although a wide entrance ensured that passersby had a good eyeful of the unattainable mirth inside. It was kind of like Johnny Depp’s climactic birthday party scene in Blow, except the waiters were not clandestine agents about to bust the revelers for violating federal good-taste statutes. For the huddled masses on The Outside, roving carts peddled $20 flutes of champagne.

Other than bypassing the huge line, the other privilege accorded by the press credential was the right to photograph the works exhibited. The door policy on cameras was surprisingly strict, and I witnessed several cases of visitors with cameras being turned away and told they needed to check their equipment at the door. Having forgotten my camera at home, I picked up some disposable 35mm Walgreens cameras and shot away, my amateurish setup drawing the unspoken ire of more than a few gallerists.

Fair point.

Fair point.

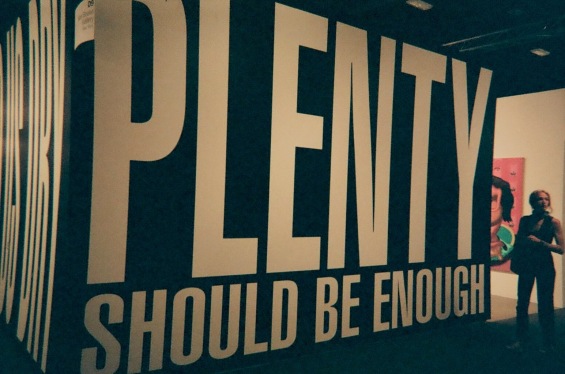

The curious thing about the prohibition on photography is that people are permitted to take pictures with their mobile devices. The halls of Art Basel and every peripheral fair I attended, irrespective of policy on cameras, were full of people snapping shots with iPhones, Blackberries, and the occasional that guy wielding an iPad. It doesn’t take a trip to the Guggenheim or a Jay-Z concert to affirm that this is now the default mode of cultural consumption, but one would think that such an avant-garde community, with its conceptual installations and all-caps slogan-art (“NO PATENTS ON IDEAS.” “PLENTY SHOULD BE ENOUGH.”) would be more open to the idea of photographic reproduction.

The photographic situation is part of a much larger tension between the idea of the visitor-as-consumer, bound within the rigid logic of commerce, and the traditional museum mode of visitor-as-student. One art installation, for instance, featured a lifelike statue of Prince William, with a diamond ring strategically placed on his forearm. Visitors could walk up to HRH, like an interactive Madame Toussaud’s exhibit, and interlock arms, slipping their ring finger into the fake-diamond-encrusted band, while their friends or loved ones captured the moment on Instagram. I watched as a particularly rowdy patron put her arms around Prince Harry in a full-on embrace, oblivious to the ring. A smartly dressed employee from the London gallery that put up the statue immediately intervened, reprimanding the lady for interacting with the piece in a non-officially-sanctioned manner.

A tender moment with Prince William.

A tender moment with Prince William.

This was not the only interaction of its kind. I found myself frequently returning to an Italian gallery’s installation of what appeared to be standard flooring tiles. These tiles occupied the outer edges of their space, i.e. bordered walkway thoroughfares on both axes. People were constantly stepping onto the tiles, both as they entered the gallery’s area and as they walked past or rounded the corner. A wild-haired Italian man, who appeared to be affiliated with the whole situation, irately told off the oblivious imbeciles. I asked him if perhaps the artists had intended this kind of “accidental” interaction when they laid out the space. In an exasperated tone he explained that this was purely incidental – the issue was that the tiles, to the untrained eye, looked like material to be tread on.

Don't step on my tiles, guy.

Don't step on my tiles, guy.

* * * * *

South Beach is perhaps not the first place that comes to mind when considering the world of high culture. The name of the event is thus a bit infuriating—Art Basel Miami Beach, sometimes truncated to Basel Miami—a perplexing string of geographic signifiers. Basel’s other recent major export is the eponymous Basel III agreement, the capital adequacy regulations designed to reign in the bank excesses behind the 2008 credit crisis. This sober tone stands in opposition to the Floridian fiscal free-for-all: Florida, along with California, led the country in subprime mortgage defaults. Miami Beach, beyond the lexicon of pastel buildings and new money, doesn’t have much else to recommend it, save for a tinny bravado. “If Miami hasn’t gotten it,” declared Vinnie in an early episode of Miami Vice, “they haven’t invented it.”

In observing the crowd at Art Basel, I returned to Saatchi’s excoriation of the event and the international scene it stands for. He wrote, “The new collectors…are reduced to jibbering gratitude by their art dealer or art adviser, who can help them appear refined, tasteful and hip, surrounded by their achingly cool masterpieces…At the world's mega-art blowouts, it's only the pictures that end up as wallflowers.” He then named the offending “conceptualized” works: “videos, and those incomprehensible post-conceptual installations and photo-text panels.” A glance at Saatchi’s artistic roster suggests some contradictions here, but who needs consistency when you can have nostalgia?

It is difficult to categorically condemn the contemporary art scene precisely because it is so balkanized—and, frankly, I did enjoy some of the work in Miami, especially at the New Art Dealers Association (NADA) fair, one of the more peripheral events. But it is easy to sympathize with the argument that the intellectual heft of the artwork has taken a backseat to the glitter impulse. Saatchi confides: “[M]y dark little secret is that I don't actually believe many people in the art world have much feeling for art and simply cannot tell a good artist from a weak one.”

Idiosyncratic objections to artistic buffoonery are common, and sometimes highly visible—Hilton Kramer left the New York Times, where he served as art critic, to found The New Criterion in vehement objection to a rising nihilism in contemporary art. More recently, Tracey Emin, one of the original darlings of the Saatchi gallery, provoked an ex-lover, the painter Billy Childish, by insulting his art as “stuck” in his antiquated choice of artistic medium. He responded by drafting the Stuckist manifesto, in which he declared: “Post Modernism, in its adolescent attempt to ape the clever and witty in modern art, has shown itself to be lost in a cul-de-sac of idiocy. What was once a searching and provocative process (as Dadaism) has given way to trite cleverness for commercial exploitation.”

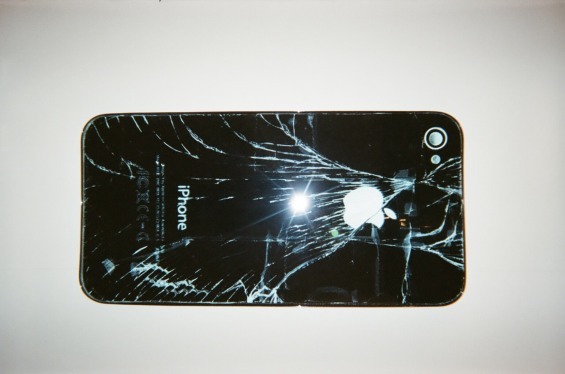

This artwork depicts the shattered verso of a massive iPhone. The picture of (post)modern loss.

This artwork depicts the shattered verso of a massive iPhone. The picture of (post)modern loss.

Hence the critics’ reproach: the curators of taste are the authors of their own undoing. It’s easy to be offended by a social situation in which few people seem to be serious students of the art world, but rather dilettantes and gadflies (yr. correspondent belonging, officially, to the lowest stratum of the latter category). Art Basel can be read as a Matruschka doll of inside jokes—on the inside, authorities and newcomers locked in a perpetual accusation of nihilism; on the outside, a cryptically silly facade. The aura of exclusion – the gated lounges, the endless line of black BMWs, and the backdrop of raucous invite-only parties – suggests to the casual fairgoer that the art itself is part of an elaborate set, and she is a duped extra.

This is the classic nightclub theory of self-worth, driven by the number of people fiscally excluded from being you. The same feeling returned later that night, as I snuck into the MoMA PS1 party at my hotel, which featured a negligibly younger iteration of the same set, coupled with the perfect backdrop of a Kim Kardashian look-a-like competition. One of the competition’s winners, who looked nothing like Kim, wore three narrow red banners that declared: “IT’S ALL ABOUT ME / I MEAN YOU / I MEAN ME.”

* * * * *

When Saatchi et al. – the old tastemakers – reigned supreme, their aesthetic was not “nihilistic” but subversive and avant-garde, in their eyes at least. Now that a new scene is in vogue, the old guard charges inelegance and artistic weakness. Yet the new and the old share more characteristics than they would admit. In this perverse game of musical chairs, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Bananas speak louder than words: a VW bus filled with the fruit, left to rot over the course of the fair.

Bananas speak louder than words: a VW bus filled with the fruit, left to rot over the course of the fair.

An unambiguous message about capital, wheat, celestial bodies, and user-friendly Linux distributions.

An unambiguous message about capital, wheat, celestial bodies, and user-friendly Linux distributions.

Back in the Hall of Champions, I picked up a copy of the Yishu Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art. The two young women at the booth explained that they were entirely unaffiliated with the journal, which is based in Vancouver, and that they work in “import/export” in New York. Go figure. The publication, also in its tenth year, featured an article by Chinese curator and essayist Zhu Qi, where he laments the Western influence in Chinese contemporary art:

“At the height of the market bubble, a lot of avant-garde artists, seemed to have become avant-garde capitalists; each one spared no expense, claiming the need to invest up to one million RMB for their own exhibitions in order for Chinese avant-garde to catch up with Western art. Avant-garde artists in the West who are ridiculed are nevertheless sought after and emulated in China. For example, many Chinese artists worship the English artist Damien Hirst, whose diamond encrusted “skull” had a price tag of one-hundred million USD. In a parallel gesture, some Chinese artists have proposed to directly use antiques as the raw material for their installation work…“

That the boilerplate pseudo-intellectualism of contemporary art has metastasized worldwide is hardly surprising. Guy Debord, in his landmark treatise Society of the Spectacle, argues that the advent of the post-industrial art museum, which makes coherent an international corpus of art, signaled the eventual demise of art as the product of a historically traceable dialogue. The impossibility of universal communication, and the subsequent splintering of artistic communities that was witnessed with the Dadaists and Surrealists, eventually gave rise to the art fairism we see today. In the art fair we see in its near-totality the contemporary art scene, a tessellation of self-referential work.

* * * * *

Just like the man barging past me in an Allen & Co. Sun Valley fleece on his way to the VIP pavilion, fur-bedecked significant other in tow, the onwards march of the moneyed but classless is an unstoppable historical force. To laugh at the foibles of this bourgeois coterie is as old as the class-system itself. It’s easy to look at the assembled group in Miami, that Las-Vegas-upon-the-Sea, and take issue with the gilded nihilism of it all. This is the voice that condemns the generally spectacular vulgarity of taste (or lack thereof) and capital (or surplus thereof) on display, a voice that announces, in a range of tongues: this scene disgusts me. It’s an entertaining exercise, and an easy way out. Getting angry about the people standing around sidesteps the fundamental issue: why so much of the art doesn’t stand for anything at all.

Not an LLC.

Not an LLC.

Like the fashion-nightlife axis with which the art scene intersects, the perspective here is highly seasonal. Much was made of the fact that this was the fair’s 10th anniversary. Perhaps by necessity, there isn’t much of a long view of history in contemporary art, or a commitment or responsibility to a particular stance on artistic production. This ideological laziness sets the stage for Saatchi’s vacant outrage. The British poet Philip Larkin, who for a time reviewed jazz for the Daily Telegraph, echoes Debord in describing "a capsule history of all arts – the generation from tribal function, the efflorescence into public and conscious entertainment, and the degeneration into private and subsidized absurdity."

In a deleted scene from Borat: The Movie, Sacha Baron-Cohen leads a Southern grocery-store clerk in a romp through the cheese portion of the dairy section. He goes down the aisle, pointing at every single product and asking, “Is this a cheese?” The increasingly confused employee answers in the affirmative dozens of times. It occurred to me, as I wandered past a huddled group of gallerists discussing “foreign currency risk,” if the same scene could have been set at Art Basel, with Borat asking, “Is this an art?” And nobody could have given him a straight answer. This global art scene, with its attendant foibles, feels like the disco culture so enamored with itself it never got around to producing something worthwhile. And like disco, Art Basel and its courtesans will be forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment